Madubuko Diakité

Contribution to The Interview Series in the form of a life story.

Historical Background

I was born in Harlem, New York and my first experience in human rights came through my mother. She was a follower of Marcus Garvey and was proud to know all the early human rights activists in Harlem at that time, which included Paul Robeson. I used to walk with her to 125th and Lenox Avenue, now Malcom X Boulevard, to listen to Carlos Cooks, a disciple of Marcus Garvey. I was young then, between 10 and 11, but I understood what Mr. Cooks was talking about, and tried to figure out how we could fight against all the injustices toward black people he and my mother talked about. My parents got divorced when I was five due to their political differences. Mom was a devoted Pan- Africanist while Dad was an American Patriot. Shortly after their divorce, my mom married a Pan-African patriot from Barbados. They had a daughter and a son, but their father died when my brother was only one year old.

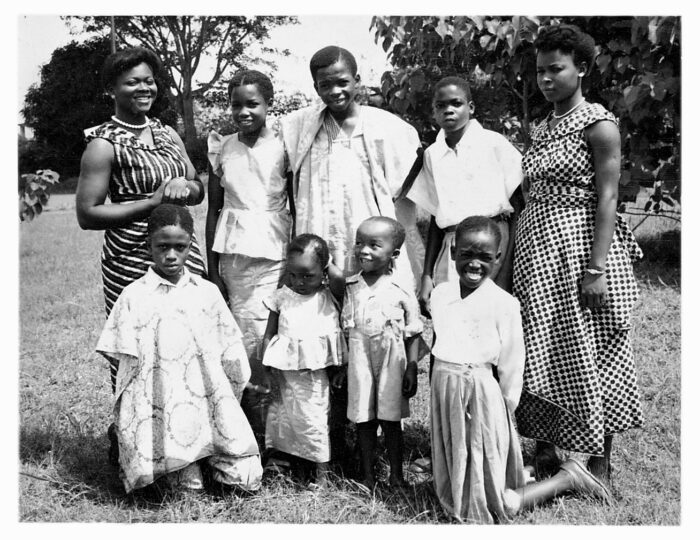

Two years later she married a Nigerian student of journalism. She then sent the four of us to Nigeria where we were to live until she joined us “soon”, as she promised. I lived with my stepfather who was one of the country’s most influential journalist. He was fighting for Nigerian independence from British rule, and I read all his newspaper articles and attended three or four meetings he held with politicians. Their struggle was with the rights to free speech, the right to vote and self-government, and I learned very much about the principles and rules of Human Rights.

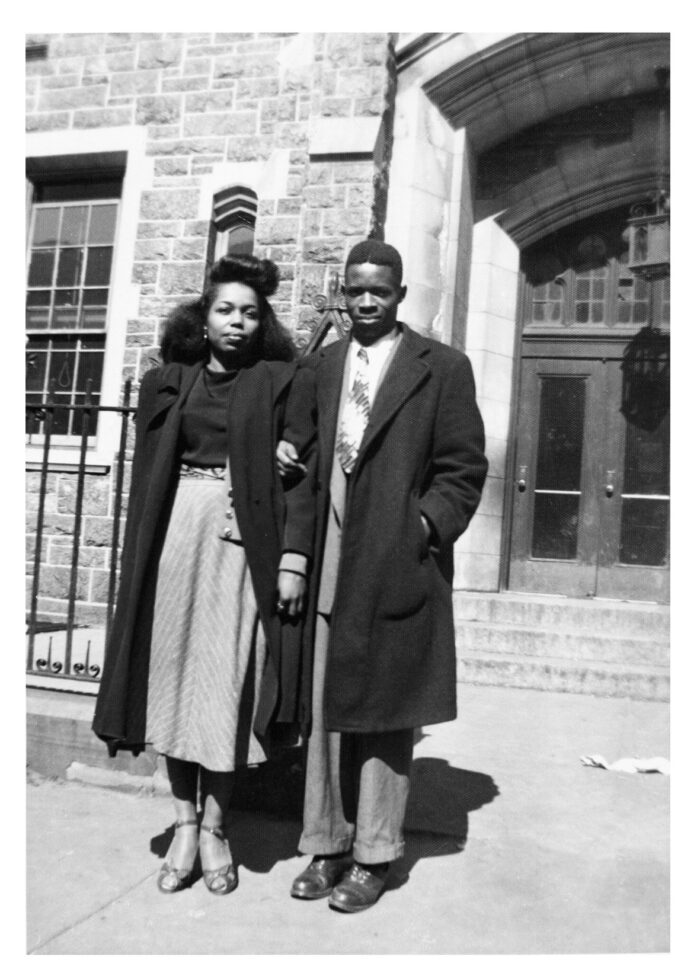

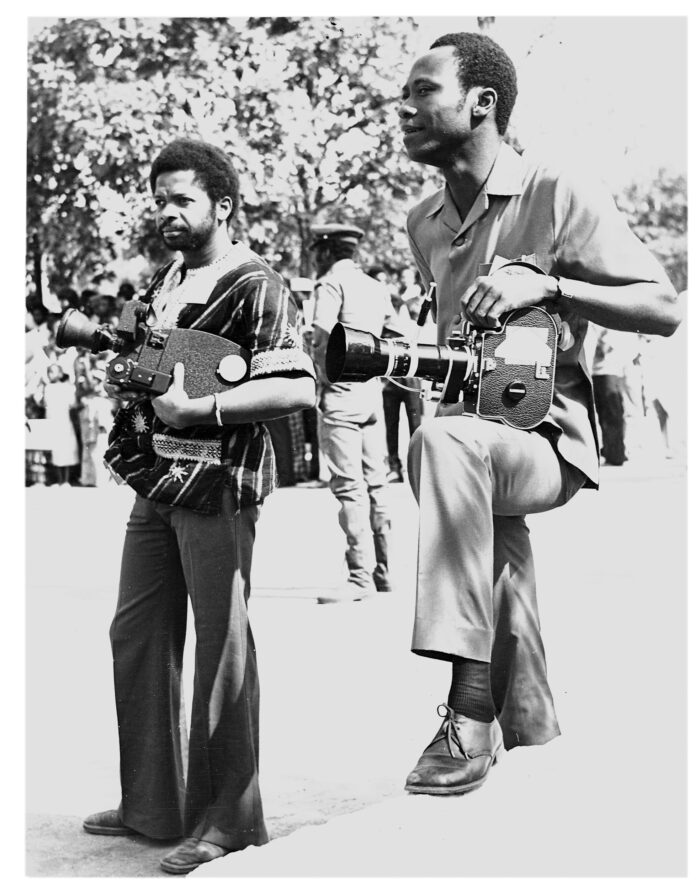

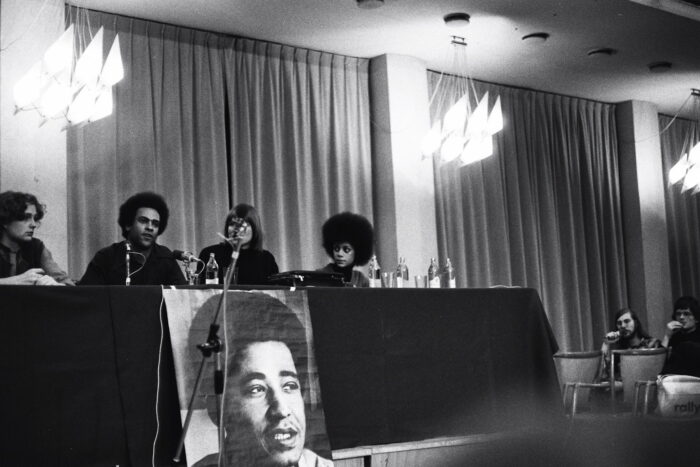

With the support of my father I returned to the United States when I was 16. I found that my mother was a civil rights and Pan-African activist and counted Malcom X amongst her friends. While working for a Nigerian NGO at the UN in New York in 1963, I briefly met Malcom X at the Diplomatic Lounge there. I was so pleased to meet him, and listened attentively as he told me to keep up my good work in fighting racial discrimination in Harlem. At the time, I was working with my mother in helping poor people find housing in Harlem while working for an NGO in Harlem called HARYOU-ACT that had projects helping African Americans register to vote in elections. I then earned a law degree in 1967 and worked for a number of insurance companies. But NYC was on fire during the late 60s as was the entire country, with the police killing Black Panthers, and local white vigilantes were killing civil rights workers in the South who traveled there to help black Americans register to vote. I quickly realized that documentary filmmaking was the best way to educate and teach people about their human and civil rights. Since my family had no money to send me to a university, and the government had no programs to send poor people to any university, I decided to leave the US in search of a film school in Europe. My fiancé at the time, Elaine Bosak of Scranton, Pennsylvania, encouraged me with my search in Europe and we flew to Paris to start my search. We started in Paris, bought a small car, then drove through France, camped out in Spain, and then parted company in Luxemburg. In my search, I looked in the Netherlands, then went on to Denmark before coming to Sweden and finally settling in Lund in September 1968.

Contemporary issues

Lund in 1968 was a very active student town with 20 thousand students. The biggest surprise for me was that students were demonstrating against the building of the nuclear power station in Barsebäck with cries and signs all over town to Stoppa Asea, the Swedish electrical company that was involved in building the nuclear station. There was another group of demonstrators called Grupp 8 that were fighting for the rights of women in Sweden. The Viet Nam and Nigerian wars were also loudly protested by many students, and the American Civil Rights struggle was also on the minds of many.

I made many great friends in Lund, and through my South African friend Hilmi Desai (now Dr. Hilmi Desai) who also introduced me to my other great friends here: Naved Rehman, a filmmaker who taught me basics of filmmaking; I also met a brilliant Tunisian student of Economic History named Raouf Ressaissi, who had huge posters of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X on his wall. He was the friend who finally explained the difference between Capitalism, Communism and Socialism to me; and a British student of political science named David Weston who confirmed his statements. All of my new friends were able to explain to me that though Sweden is known for its cradle to grave care, child and housing subsidy, and free university education for all, including immigrants, racial and sexual discrimination were rampant throughout the country. They added that racial discrimination is rampant in employment, the police, and other structures of Swedish society, and that local politicians were not at all on board with the human rights treaties Sweden has ratified. Above all, they told me, foreign students were seriously discriminated against in housing and education here in Lund. They gave me several concrete examples of cases of structural discrimination in Sweden, and with that evidence I went straight to Swedish TV2 in Malmö with a project on how to make a documentary film on structural discrimination in Lund. The film was produced by Herbert Söderström, and narrated by Gary Engman, both of them now long deceased.

The documentary was entitled “Det Osynliga Folket” (The Invisible People,1973), which told the story of several cases of structural discrimination in Lund at that time:

1. There was a Middle Eastern Student who was told by the police that the “UT” stamp in his passport stood for his being sent out of the country, when in reality it was a stamp showing that he had applied for an “Uppehållstillstånd” (resident permit).

2. Four university officials spoke honestly and openly about how difficult it was for foreign students to understand the language in the strange brown envelopes from the police, the social bureau or the university regarding dates for appointments, examinations, or just general information.

3. The strange case of an African American student who the police deported before any decision about his residence status had been made by The Swedish Migration Board. He immediately returned to Sweden after going to the Consulate in New York where he was told that he was not deported but in fact had a residence permit waiting for him at the local police station in Lund. He was away for only 3 weeks and returned to his girlfriend who was awaiting their child. But no policemen were addressed about their error in judgement to deport the student.

These and several more cases were outlined in the film. The results were that there were several debates on TV2 about the situation for foreign students in Lund. The major result at the time was that they temporarily moved the Police office for foreigners to a separate location for some five years, only to move it back to the old station house, where it remained until they opened the Swedish Migration Board.

The future

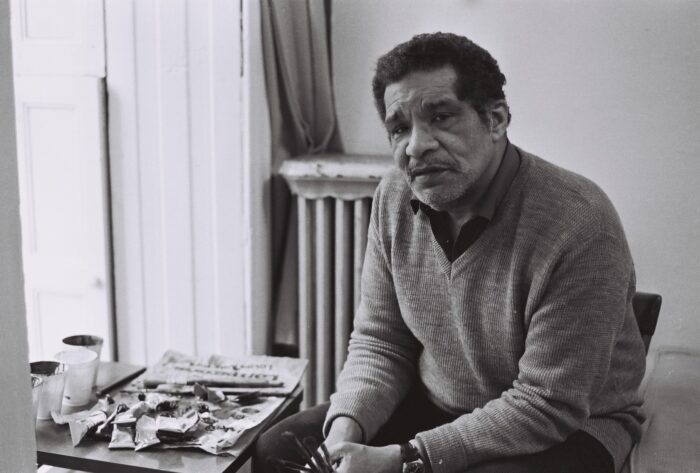

During my residence in Lund during the 70s, 80s and 90s I was continually at the forefront of promoting human rights. My Master’s degree thesis at the Raoul Wallenberg Institute examined racial discrimination in labor in Sweden, and I was active in various organizations dedicated to the struggle against racial and other forms of discrimination in Sweden and in Lund. In the late 1980s I started publishing a newsletter in English for all readers living in Lund and worked with local high school teachers, students, and other volunteers to produce the articles and photographs. The magazine was entitled The Lundian Magazine and it featured photos and articles about life and people living in Lund. My work was featured in Volume 3 of Lunds Historia – Staden och omlandet, Modern Tid, which was edited by history Professor Sverker Oredsson. It is available in Lund’s public library (Stadsbiblioteket), amongst others.

In the mid-1990s, I attended a Lund conference on integration held in Hörby where I constantly reminded city officials that our city needs an anti-discrimination bureau, such as the one currently running in Malmö. But Lund’s solution was to establish an office within a small department within the County. It was only when the now defunct Board of Integration (Integrationsverket) in Norrköping provided my NGO network, the English International Association of Lund, that we were able to establish the first strong anti-discrimination bureau for everyone in Lund. The bureau had an office in ABF house on Kiliansgatan 13.

Before it closed in 2005, I asked for funds to continue it from all of Lund County politicians at that time but the only one who gave a promising answer to my request was the Centre Party. So, without any County government support, the anti-discrimination bureau, which was open to all persons in Lund closed. But my struggles in Lund continued.

In 2011 Swedish students at a Nations Hus held a mock slave auction which angered many foreign and domestic students. One student, who had contacts with the Rev. Jessie Jackson called and asked him to come to Lund to give support to those of us fighting racial discrimination here. He came and addressed the entire student body and faculty at the main university building (known locally as the White House), and at the Law Faculty urging all of us to cooperate peacefully with one another. My comrades Daniel Eklöv, Elaine Bosak, Monique Fransen and I attended several meetings and conferences with Mr. Jackson in Lund and Malmö. A human rights law professor from the United States, Mr. Clifford Johnson, gave lectures on affirmative action at the law faculty, and was joined by Professor Dennis Nordin in helping solve the issue of racial discrimination at Lund university. And my collogues Elaine, Daniel and I had a meeting with the rector of the university to ask if the students that held the mock auction of slaves would be censored or spoken to. But the reply we got from the rector at that time was that their actions were not harmful to anyone, and that he would speak to them. But there is a serious vacuum in Lund on the question of human rights protection for all persons living here, despite the fact that the city proudly wears the crown of “Human Rights City”. But the crown and the title are false. When I learned that there was a movement amongst academics to award Lund with that title, I was furious. Of all the cities in Sweden that deserve such a title, Malmö stands head and shoulders above Lund. Lund has no anti-discrimination bureau where all persons can report their grievances. But Malmö does.

After completing my Juris Licentiate degree at Lund University School of Law, I decided that I could not live at peace with myself in this town because it had little alternatives for persons who suffered from one of the United Nations major cornerstones of human rights: racial discrimination. Lund can’t have much of a good future unless all forms of discrimination are treated equally and fairly. And I can’t live here if race, or ethnic discrimination is not amongst those that the town prefers to protect citizens against.

I love the city of Lund, but if it is going to have a successful future it must establish and support an anti-discrimination bureau for all persons living here, not just for a few academics. Until then, it will continue to lose good minds and good people for other places in Sweden. Such as Malmö.

About Madubuko Diakité:

Madubuko Diakité was born in Harlem, New York and now resides in Malmö, Sweden.

Hunter College, New York: General Studies (no degree)

Stockholm University, Sweden: Master of Arts: Black Filmmakers in Africa and the USA.

Stockholm University, Sweden: Doctoral Research in Film Studies (ABD)

Lund University Faculty of Law: Jurist Licentiate: Legal Protections for migrants in Africa

Lund University: Raoul Wallenberg Institute of Human Rights Law, Lund, Researcher Emeritus