Michael McEachrane

Black Archives Sweden has spoken to Michael McEachrane about his family archives.

How do you work with (relate to) your family archive: photographs, films, sound collections, memories, oral histories?

To muse a little, my largely uncollected and uncurated family archive is itself illustrative of a diasporic condition of dispersal and makeshift. Collecting and sorting out what is left of the family archive is one of those future projects I have wanted to do for a long time, but have not yet gotten around to. Dad took quite a lot of Super 8 footage of the family in the 1970s. He interviewed his mother/my grandmother in Tobago and others here in Sweden, England and elsewhere (on one of those portable cassette tape recorders with a shoulder strap and a microphone journalists used to use back then), and there are some pictures of the family taken by him, mum and others. Some of this is in two photo albums mum has. But some of this material was destroyed when my brother Sonny’s storage room was broken into, with boxes we had retrieved from dad after he passed away in 2000. Some of the Super 8:s should be in a storage room of a cousin of mine, Sandra, in Brooklyn (probably now in bad shape after I left them there when I moved from NYC to Amherst in 2008). And some pictures should be in a box somewhere in mum’s storage room in the basement of her apartment building in Lund.

You have shared with us a visual material that is connected to your family. Why this particular material?

These are the pictures that I could find, which I thought tell a representative story. The first picture, from one of mum’s two photo albums, is of my grandmother, Isabelle “Bell” Miller McEachrane. It was probably taken in 1968, on the veranda to her house in Calder Hall, Tobago. I have never heard anyone express anything but deep gratitude and respect for her. She had a calming hard-to-put-into-words presence of openness, acceptance and integrity. One of my strongest childhood memories is Bell singing, telling stories and praying with us, myself and Sonny, at bedtime.

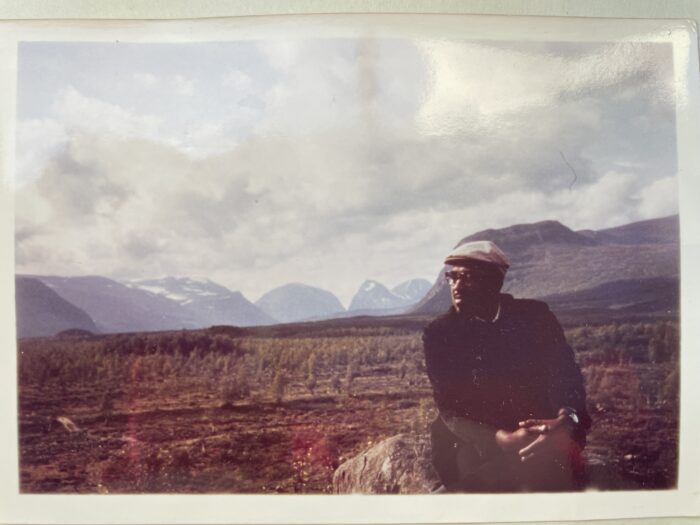

The second picture, also from one of the albums, is of dad outside Kiruna in the very north of Sweden in 1968. It was taken when they were there for their wedding, with the sort of Northern Swedish mountains (“fjällen”) in the background that mum used to love to hike in. Mum and dad met at a pedestrian crossing in London in 1967, when dad lived there and mum visited as a tourist. They lived in London for two years, married in Kiruna in 1968 (according to the newspapers, dad was then the first Black man to marry in Norrland), and moved to Ängelholm in 1970—a few months before I was born.

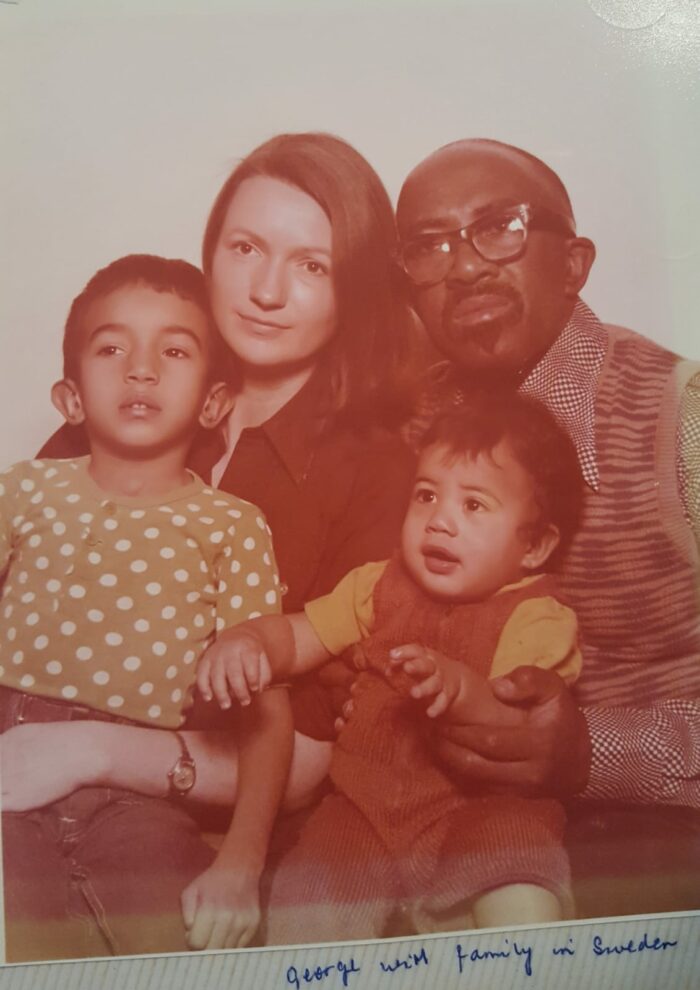

The third picture is of the whole family, with me in the white-dotted green t-shirt, probably taken in 1976. It was recently shared with me on WhatsApp by a cousin of mine in Canada, Arlette.

Dad, George Horatius Whitfield McEachrane, was born in Tobago in 1929 and passed away in Malmö 2000. He moved to London in 1960 or 1961, before Trinidad and Tobago became independent from British colonialism. He therefore kept his British citizenship, which myself and my brother inherited by birth in Sweden, me in Ängelholm in 1970 and Sonny in Malmö in 1974. I recently got Swedish (dual) citizenship the other year and have yet to collect my Swedish passport. Mum, Kerstin Charlotta Alsund, was born 1942, and raised in Kiruna by a dad who was a Tornedal Finn (who changed his last name from Pudas to Alsund) and a mum from Värmland in the southern part of the country.

There were two more pictures that I had really wanted to show instead of the first two ones. Hopefully, I’ll find them in a box one day. One of the pictures was taken in Rosengård in Malmö 1971 or 1972. It is (or maybe was) a black and white picture, taken on the balcony of our apartment on the seventh floor of a building still colloquially called “the Chinese wall” because of its winding length. In the picture you can see dad in the foreground looking somber at a table with a radio on it (maybe with the English speaking BBC World Service on), and next to him a blond boy, Christian, the son of a cousin of mum. In the background you can see a vast desolate looking space with construction cranes in the distance, building away towards the million new homes that the Social Democratic government had promised to build between 1965 and 1974. Rosengård and all the other “million program” areas around Swedish cities soon became and are still viewed as dominated by immigrants, people of colour and social problems, especially with the sharp rise in gang-related violence. I grew up in “million program” areas in Malmö: Rosengård, Bellevuegården and Kroksbäck.

The other picture is (or maybe was) of the store Afro-Asian Center, which dad and mum ran in Malmö from 1977 until 1986. First on Davidshallsgatan 1977-1980, Gustaf Adolfs torg in the heart of Malmö 1980-1984—where the picture I have in mind was taken—and then on Södra Förstadsgatan 1984-1986.

The store sold clothes and other items from what was then called the “Third World”. It was probably named after the critical anti-colonial Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung, Indonesia, in 1955. I have a vague memory of my dad and some of his Caribbean friends, sitting in our kitchen discussing what name to give the store. It could have been one of those conversations when I heard such names as Marcus Garvey, CLR James, George Padmore and Walter Rodney, mentioned in passing, but in such a way that one understood that they must be of great importance. Dad had always had a defiant, anti-colonial spirit about him. For example, there is the story of how he as a young man tore down images from Bell’s walls of a white Jesus and the British royal family. However, being in Sweden which he experienced as profoundly alienating — and I do too even if perhaps not for the exact same reasons— seemed to “radicalize” him in some ways. For example, he stopped wearing suits, white shirts, and ties, shaved his head and began wearing dashikis, even during the winters, but with a polo neck underneath. He made a point of not subserving himself to what he thought were white norms. It is no doubt that my own interests in postcolonialism and Pan-Africanism are inherited from him.

What does the (black) archive mean to you?

I love what you are doing with Black Archives Sweden. Our stories need to be told, carefully collected and curated. Our stories and experiences are not a part of and not told by the mainstream with its “ethnocentric” narratives. Black Archives Sweden is a way of breaking the silence, invisibility and marginalization—carving out a space where the voices and histories of Black people in Sweden can be heard, collected and kept for present and future generations.

Thank you, Jonelle, Ulrika, Anthia and Joella for the work that you do.

About Michael:

Michael McEachrane is a researcher and activist. Among other things, he is the co-editor of one of the first, if not the first book with a postcolonial perspective on Sweden, Sverige och de Andra: Postkoloniala perspektiv (Natur och kultur, 2001) and the first Black Studies book on the Nordic region, Afro-Nordic Landscapes: Equality and Race in Northern Europe (Routledge, 2014). As an activist he has been involverad in the creation of several organisations such as the European Network of People of African Descent (ENPAD), was deeply involved in the establishment of the UN Permanent Forum of People of African Descent and is currently a board member of Black Lives Matter Sweden (BLMSWE).